Archive

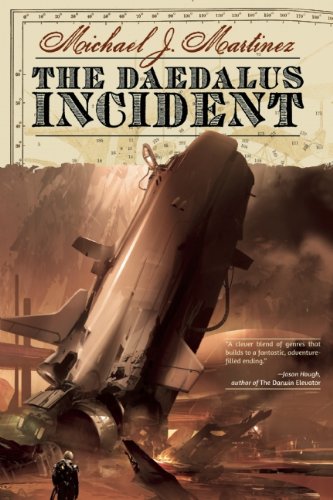

The Daedalus Incident by Michael J Martinez

We’re back to the age-old question of what we should be looking for when we read a new book. I suppose we want some degree of novelty or originality. After a while, reading and rereading all the most obvious plots and tropes become boring. So it can break the monotony when someone tries something new. Let’s start off with the solar sail. This used to be quite a common idea to play with. Our space vessel would literally spread its wings and the currents of space would drive the ship forward. Hence, for example, David Weber uses gravitational sails and has “naval engagements” in his Honor Harrington series, while David Drake’s RCN series more explicitly has space ships with rigging that has to be stripped down before the ship can enter an atmosphere. Following in the same tradition, Bob Shaw has wooden spaceships crewed by ragged astronauts in the Land and Overland Trilogy. In Philip Reeve’s Larklight series, the alternate history context is provided by a British Empire now encompassing the solar system with Victorian sailing vessels powered by alchemical engines, cf the Spelljammer gaming universe.

I could go on but you should get the message that one of the two narrative threads in The Daedalus Incident by Michael J Martinez is just channelling Patrick O’Brian and recycling Philip Reeve and the film Treasure Planet (I also note a later form of shipping in a paddle steamer which appears in The Fifth Element). This latest contribution to the trope changes the alternate history context to a British Empire sailing into space using eighteenth century naval ships of the line given breathable air and gravity through alchemy. So literally half this “new” book is a rehash of old plot ideas with eighteenth century British naval life extended to include outer space and the planets which are all habitable with at least two alien species of different levels of technology established on different planets and moons. As with the majority of such space fantasy plots written during the early twentieth century, we even have a pirate ship which ferries the primary antagonist around the solar system. Although some of the detail is quite well worked out, this half of the book is rather tedious and wholly derivative. I might have forgiven the almost total lack of originality if either the plotting had been wildly inventive or the writing intentionally humorous, but the plot has nothing new and it’s written with a completely straight face. It even plays the same game as Ronald W Clark in Queen Victoria’s Bomb in which famous historical characters appear, do their thing for a few pages and take a quick bow. We should be grateful American presidents don’t break off their parochial concerns to start killing vampires.

The second half of the book is set in the twenty-second century on Mars with the Joint Space Command using hard science to move between the planets while commercial interests extract minerals from Mars. The tension between the military and business factions is routine. When there are unprecedented seismic events, the security forces want the mining operations suspended. Not caring how many men may be injured or killed, the hard-nosed capitalists insist on “dig, baby, dig!” Needless to say, the future world of conventional science soon collides with alternate history world of alchemy in a multiverse plot. An alien is trying to break out of an interdimensional prison and breaks down the barriers between our two human-dominated dimensions with entirely predictable results.

It’s possible to pull of such a conflation of different plot elements when the author has wit and verve. Sadly, all this is plodding and predictable. Worse, the fact-checking is deficient with a cricket match overseen by a referee. That’s like having a baseball match mediated by a judge. When Night Shade Books was collapsing financially, it seems to have bought up the rights to some first novels. They are cheap and, in an undiscriminating market, can occasionally hit the jackpot — all authors have to start somewhere. As part of the settlement with creditors and authors, Skyhorse is honouring existing contracts on modified terms. Hence The Daedalus Incident sees the light of day. Hopefully, Skyhorse will soon take a grip of the editorial process and improve the standard of the books it buys. In this I note the complete lack of information on the website under the Night Shade banner. It might gives us all greater confidence if the new owner would communicate with its readership.

A copy of this book was sent to me for review.

Blue and Gold by K J Parker

It’s curious how, when you grow old, you lose that questing spirit of youth. I used to range far and wide in search of new and interesting writing talent. Now I have to wait for someone to hit me over the head and tell me to try an author. In this case, no-one seems sure who it is — apparently it’s a kind of Alice Sheldon situation with an author jealously guarding anonymity. Anyway, no matter who this is, he or she writes beautifully. I’ve just charged through Blue and Gold (Subterranean Press, 2010) by K J Parker. It’s a delight. I’m increasingly impressed by the Subterranean series of novellas and, to improve my mood, it turned out there were two more short stories by said Parker on Subterranean’s site. So I got three for the price of one — great value!

This is an unreliable narrator story which, if done well, is among the most interesting to read. By their nature, a puzzle is presented for the reader to solve. Why is it this particular character has a need to lie or feels the need to conceal his or her essential nature. This ignores the less interesting variations where the character is plainly less than sane. It’s bad enough trying to make sense of my own tendencies to irrationality as my body weakens and mind degrades through age. Being invited to look inside the mind of a fictional character with a similarly weak grasp on reality is not attractive as a mirror to my own problems.

So, from the first page, we have this first-person narrator, one Salonius, assert with pleasing honesty that, in the morning, he cracked the age-old problem of how to turn base metal into gold and, in the afternoon, murdered his wife. Obviously, for some, this is the ideal way of celebrating the sudden acquisition of unlimited wealth. Who wants to share all this gold with anyone who would only waste it on herself? Except, as the book progresses, we discover this was no ordinary death. Nothing so crude as an attack with a blunt instrument, you understand. And not a death motivated by gold, of course. Everyone knows it’s impossible to change base metals into gold. So here we are with the undoubted fact of a death and no clear understanding of how and why it should have occurred. What makes this even more surprising is the reaction of her brother, one Phocas who, courtesy of an outbreak of a virulent disease, skipped over the normal rules of succession as relatives closer to the local throne fell by the wayside. Why should the local ruler. . . Well, there do seem to be local political difficulties but, for now, he’s more or less in charge. So why should a loving brother be prepared to forgive our narrator for the death of his sister. Ah, yes, I did forget to mention that Salonius was married to the ruler’s sister. Sorry about that. I’m an unreliable narrator as reviewer, you see.

One thing rapidly becomes clear as you read this delightful little book. Salonius is a bright and intelligent person. In fact, he’s probably too bright for his own good, what with this demand for alchemists who can rustle up useful stuff like gold. In career terms, this is somewhat confusing because he never intended to become an alchemist. Like spending some time as a thief, it was a profession he drifted into as the need arose. He probably should have become one of these ivory tower professors who spend their years musing over problems with no obvious solution, writing impenetrable monographs no-one would ever read. But his life was never destined to be quiet. He was always going to make a name for himself, one way or another.

The story is a particularly pleasing slow reveal of the broader circumstances leading to the death of his wife. I was entranced by the author’s sly humour. Not in the sense of jokes, you understand. No, nothing so crude as jokes. The humour arises from the cut-throat nature of the society being described. If an intelligent man is not only to survive but make money, he needs to develop problem-solving skills. Solonius demonstrates a mastery of the obvious trick.

Some years ago, I had the good fortune to know a professional sleight-of-hand magician. He could make a variety of small objects appear and disappear in the most surprising ways. Having seen one or two of the manipulations in slow motion, I can attest to the fact he had great skill. But even seeing a trick deconstructed, I still have no clear idea how he did it. The level of physical dexterity was beyond belief. As a dispassionate observer, you know it’s not magic. After all, like alchemy, you know there’s no such thing as magic. But there are times when you encounter skill levels so high, you would like to believe magic is real. So Salonius makes people around him want to believe. Even when he tells them the truth — that it’s impossible to turn base metal into gold — they still gather round to see the trick one more time.

I cannot recommend Blue and Gold too highly. When I have a little more time, I’m going to read it again, just to remind myself how the trick is done.

For a review of another novelette published by Subterranean Press, see Purple and Black. There are also a standalone novel Sharps and a collection Academic Exercises.

The Alchemist’s Code by Dave Duncan

And now it is time to sit down for that second cup of my grandma’s tea (see The Alchemist’s Apprentice). There are times when I reach the end of a mystery book and the detective does the final “reveal” leaving the criminal a quivering wreck and I think, “Wow, that was really underwhelming!” I look back at the cardboard cut-out characters who were shuffled around the page to create the illusion of a puzzle and frankly, like Rhett, I don’t give a damn. Thank God for books like The Alchemist’s Code by Dave Duncan.

This is probably the most difficult of books to write — the second in what looks as though it may become an ongoing series. Let’s look over the author’s shoulder. He or she knows exactly what went into the first book and this was a success. So the first question is how much backstory to include in the second. You cannot assume that all the readers for the second volume will have read the first, but the more you repeat what happened in the first, the more you may bore the “old hands”. Duncan takes the bold route of assuming everything and plunging happily into the story. When some explanation is required, it is dropped unobtrusively into the text as we go along. This first step is encouraging.

He then produces an immediate statement of intent in the first major set-piece encounter between the Sanudos (the clients) and the two main characters Maestro Filippo Nostradamus (the detective) and Alfeo Zeno (the put-upon factotum). It is a delight to observe the dissection of the thought processes that go into impressing (or gulling) the clients.

Having settled into his rhythm, Duncan then sweeps us through a somewhat more violent and dangerous outing than the first volume. There is swordplay and a more positive supernatural element. We have the same tarot and use of a crystal ball, but there is a real jinx blocking progress in the investigation with an interesting confrontation. More importantly, the political framework of the story is much more powerful and, even though some of the history is distinctly of the cod variety, it contributes beautifully to the content for the problem and its resolution.

Back to the ending. Absolutely everything about this particular solution is meticulously set up and then explained. It is so completely a part of the milieu of Venice that it is obvious once it is pointed out to you. But it is one of the few solutions over my reading past that has evoked genuine admiration. The only other author who consistently produced a similar response is Anthony Price. The cleverness of the misdirection in some of the Dr. David Audley novels is unsurpassed. In this case, I immediately read the last few chapters again to enjoy it all over again.

Overall, this is far better than the first and can be read as a stand-alone. A positive joy in every respect. The next in the series is The Alchemist’s Pursuit. There’s a new series starting with Speak to the Devil and When the Saints, and a stand-alone called Pock’s World.