Archive

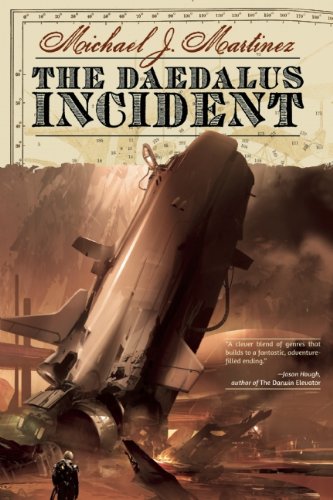

The Daedalus Incident by Michael J Martinez

We’re back to the age-old question of what we should be looking for when we read a new book. I suppose we want some degree of novelty or originality. After a while, reading and rereading all the most obvious plots and tropes become boring. So it can break the monotony when someone tries something new. Let’s start off with the solar sail. This used to be quite a common idea to play with. Our space vessel would literally spread its wings and the currents of space would drive the ship forward. Hence, for example, David Weber uses gravitational sails and has “naval engagements” in his Honor Harrington series, while David Drake’s RCN series more explicitly has space ships with rigging that has to be stripped down before the ship can enter an atmosphere. Following in the same tradition, Bob Shaw has wooden spaceships crewed by ragged astronauts in the Land and Overland Trilogy. In Philip Reeve’s Larklight series, the alternate history context is provided by a British Empire now encompassing the solar system with Victorian sailing vessels powered by alchemical engines, cf the Spelljammer gaming universe.

I could go on but you should get the message that one of the two narrative threads in The Daedalus Incident by Michael J Martinez is just channelling Patrick O’Brian and recycling Philip Reeve and the film Treasure Planet (I also note a later form of shipping in a paddle steamer which appears in The Fifth Element). This latest contribution to the trope changes the alternate history context to a British Empire sailing into space using eighteenth century naval ships of the line given breathable air and gravity through alchemy. So literally half this “new” book is a rehash of old plot ideas with eighteenth century British naval life extended to include outer space and the planets which are all habitable with at least two alien species of different levels of technology established on different planets and moons. As with the majority of such space fantasy plots written during the early twentieth century, we even have a pirate ship which ferries the primary antagonist around the solar system. Although some of the detail is quite well worked out, this half of the book is rather tedious and wholly derivative. I might have forgiven the almost total lack of originality if either the plotting had been wildly inventive or the writing intentionally humorous, but the plot has nothing new and it’s written with a completely straight face. It even plays the same game as Ronald W Clark in Queen Victoria’s Bomb in which famous historical characters appear, do their thing for a few pages and take a quick bow. We should be grateful American presidents don’t break off their parochial concerns to start killing vampires.

The second half of the book is set in the twenty-second century on Mars with the Joint Space Command using hard science to move between the planets while commercial interests extract minerals from Mars. The tension between the military and business factions is routine. When there are unprecedented seismic events, the security forces want the mining operations suspended. Not caring how many men may be injured or killed, the hard-nosed capitalists insist on “dig, baby, dig!” Needless to say, the future world of conventional science soon collides with alternate history world of alchemy in a multiverse plot. An alien is trying to break out of an interdimensional prison and breaks down the barriers between our two human-dominated dimensions with entirely predictable results.

It’s possible to pull of such a conflation of different plot elements when the author has wit and verve. Sadly, all this is plodding and predictable. Worse, the fact-checking is deficient with a cricket match overseen by a referee. That’s like having a baseball match mediated by a judge. When Night Shade Books was collapsing financially, it seems to have bought up the rights to some first novels. They are cheap and, in an undiscriminating market, can occasionally hit the jackpot — all authors have to start somewhere. As part of the settlement with creditors and authors, Skyhorse is honouring existing contracts on modified terms. Hence The Daedalus Incident sees the light of day. Hopefully, Skyhorse will soon take a grip of the editorial process and improve the standard of the books it buys. In this I note the complete lack of information on the website under the Night Shade banner. It might gives us all greater confidence if the new owner would communicate with its readership.

A copy of this book was sent to me for review.

Necessary Evil by Ian Tregillis

To get any value out of this concluding volume in the Milkweed Triptych, you should have read the first two books in order. I can say without fear of contradiction you will not understand a lot of what happens without knowing what has gone before. Ironically, the same applies to this review. I’m not going to repeat the discussions set out in the first two reviews. I’m going to focus on this book.

In Bitter Seeds, the first book by Ian Tregillis, the question is what the precog has foreseen. The Coldest War answers this question and tell us what she proposes to do about it. This leaves us with Necessary Evil (Tor, 2013) which allows us to watch how her grand design works out. From the outset, we’ve been considering whether any of these alternate timelines is deterministic. The presentation has suggested only one person has free will. Given the breadth and depth of her ability to foresee the future and pick which timeline to follow, the precog has been charting her path through the decades. In a multiverse, every decision point branches, casting off alternate realities but, up to this point, everything has worked out exactly as she has foreseen. Indeed, what she’s achieved is breathtaking. Given the scale of what she wanted to avoid, she’s had to work backwards from the one route to salvation and examine all the decision points to see how she can get there. In so doing, she’s been reviewing a potentially infinite number of alternate histories, seeking out the key moments and identifying the people she needs to influence into acting or not acting. Of course, I could invert this and say her fate was set when she was born. She was always going to arrive at the point representing the end of book two. She merely had the illusion of free will.

This would suggest others might have free will or that no-one ever has free will. But if that were the case, the very idea of a multiverse would be a paradox. If no-one ever has free will, there can be no alternate timelines. There could only be the one timeline that everyone is predestined to follow. This leads me to major problems with the plot. If this book deals with an alternate history timeline, the two people who are sent to this 1940 are from outside this timeline’s cause and effect. What has happened to them in their own timeline remains because it has already happened. It cannot be undone when the cause does not occur in the new timeline. Yet Ian Tregillis wants to play fast and loose with this issue. In this book’s timeline, the man who should survive to send them back in 1963 dies in 1941, yet the older Marsh remains in this timeline. But when the younger Marsh does not suffer the leg injury, the travelling Marsh’s leg is cured. You think that’s bad? Well here comes the nail in the coffin. In this timeline, there are two versions of Marsh but only one precog. If we have an older and a younger Marsh, why do we only have one young precog? What happened to the older version of the precog when being transported back? It’s this lack of attention to the logic of the plot that completely spoils the effect.

So putting that to one side, what are the consequences when the precog is to some extent able to reset the clock? In theory, this new timeline should unfold according to the master plan. The younger version will guide events to avoid the catastrophe she has foreseen in all the other timelines. This timeline will survive. Except, of course, there’s one small change. Up to this point, she’s been the only one with an overview of time. Now there’s a second person and he understands both the strengths and weaknesses of the precog. So he can share the precog’s desire to avoid the looming catastrophe, but not be prepared to pay the same price to achieve it. More importantly he can also work backwards and understand what would need to happen to ensure the safety of those he cares about. Ah, so now we come to the heart of the Triptych. From page one of Bitter Seeds, we’ve been watching how individuals have reacted when they learn the price to pay to get the results they want. At a national level, governments at war cannot be concerned about the individual. They are fighting for the majority of their citizens and if that means sacrificing the few, that’s a price worth paying. At the other end of the scale, the individual wants to survive but may be prepared to sacrifice him or herself if the price is right. So a loving father might sacrifice himself to save his child, a spy threatened with capture might commit suicide to avoid betraying his country.

Of course, this is talking about sacrifice in physical terms but individuals may also sacrifice their principles if that’s necessary to save themselves or others. Hence, the title of the book. History shows us that some people have fought with honour, maintaining their personal integrity and protecting the reputation of their country for fair play. History also shows how often those who play fair are beaten by those who ignore the rules of chivalry and play to win regardless of the cost. It’s been a sad theme to see how often the honest are surprised by the extent of the dishonesty around them and how easily that dishonesty can strike them down. So an individual who recognises the full extent of all the risks may well be put to the choice. When there are dishonourable options, will the decider pick the least evil or do what’s necessary to win?

You’ll have to read the book to see how it works out but, as you might expect, it’s not clear cut. When we all know exactly what price has to be paid for ultimate success, there’s a certain degree of irony in how the final element of the price is collected. Perhaps that’s how fate actually works. If there’s a sine qua non and several people are aware of it, it doesn’t matter who fulfills the condition so long as the precondition is met, i.e. the necessary evil occurs.

This leaves me with an issue I referred to in the first review but it grows significantly worse in this book. Let’s start with the practicality of life described as Britain in 1940. Early on, our hero from the future needs some local cash so he gets on a bus with some future bank notes in his wallet. The idea that a bus conductor could change a five pound note is absurd. Ignoring the physical difference in the size and colour of the future note which would be spotted immediately, the average annual pay in the UK in 1940 was about £200. So even on the busiest routes, no conductor would collect and keep more than £5 in loose change. That’s 1,200 pennies except the average bus fare around that time was a hapenny (i.e. £5 = 2,800 coins). So the conductor would be weighed down with farthings and hapennies, perhaps some thrupenny bits and sixpences, and the occasional shilling. During quiet times, the conductors used to bag the excess loose coinage and either lock it in a cabinet in the stairwell or give it to the driver for safe keeping in the front cab. Even if this conductor had enough to give change for more than one’s weeks pay, consider how long it would take to count out more than one thousand coins and how much they would weigh. This is symptomatic of a cavalier attitude towards all things British, particularly its language. I know and appreciate that this is a book written by an American for the American market, but it’s aggravating that the vocabulary and vernacular attributed to British and German characters comes out as modern American English. Scattering one or two British colloquialisms does not make this book even remotely realistic. Oh but wait. This is fiction so it doesn’t have to be credible.

I was really looking forward to reading Necessary Evil but the reality has proved a major letdown. Once you set out to write a time travel or multiverse story, there are rules to be followed. This happened in the construction of the first two books. It’s such a shame the rules were mostly thrown away in this concluding volume. If I’d known it was going to be this bad, I would never have paid for my own copy.

For reviews of the first two in the series, see Bitter Seeds and The Coldest War. There’s also a free-standing Something More Than Night

Source Code (2011)

For once we’ve got a reasonably intelligent science fiction film rather than an excuse for poorly realised spaceships to dodge and weave about the screen, firing off superweapons and exploding in balls of fire — something that suggests there’s a previously unrecognised mass of oxygen in outer space capable of supporting combustion. Well, perhaps that’s a slight exaggeration since space opera is moderately rare in the cinema these days. Hollywood prefers the cheaper version of aliens running around, blowing stuff up on Earth. That makes for better explosions and cheaper CGI. Anyway, Source Code (2011) offers us one of the more coherent efforts at a multiverse story even if it’s more than a little amoral.

No, really? A multiverse story? What’s that?

Well, before we get into spoiler territory, let’s deal with a little of the background. This theory suggests we have more than one reality. Conventional physics says time, gravity and all the other constants move in a straight line. So although each individual makes choices, the outcomes to all the decisions are fixed in the one timeframe. We all live with our triumphs and mistakes equally. But others suggest each decision is like a fork in the road. Sometimes we walk left, sometimes right. So in parallel dimensions, we live out our lives with each set of choices. In the most interesting of these theories, there are an infinite number of possible universes because, over time, millions of us make decisions every day and so the number of possible outcomes expands without limit.

OK, taking this as our base, we assume that, at any one time, there are an infinite number of realities almost exactly the same as ours shading to realities nothing like ours. Dr Rutledge, played with introverted intensity by Jeffrey Wright, has developed a technique for implanting the mind of a man from our reality into the body of a matching man in an alternate reality. If you recall Quantum Leap, we’ve the same convention that Jake Gyllenhaal is transplanted into a different body, but we continue to see Jake Gyllenhaal. This form of the transplant keeps his female fans happy and lasts for exactly eight minutes, at the end of which the host dies (not through the shock of becoming Jake Gyllenhaal, you understand, but in an explosion).

For those who like to play around with the ideas, the death of everyone on the train in this alternate reality prevents there being any contamination of that timeline. Even though the transplanted man may say or do things to disturb the alternate, the effect never leaves the train. Dr Rutledge assumes that if our hero, Colter Stevens played by Jake Gyllenhaal, can identify the bomber in the alternate reality, the same person, driving an identical van with the same number plate can be arrested in our reality and so prevent a second explosion, this time a dirty bomb.

It’s actually better not to think too much about this because the chance of people in alternate realities having the same name or the same licence plate on their vehicles seems remote. I suppose this may occur because the source code recreates a “captured” version of the alternate reality every time the program is run, i.e. it starts with the same parameters every time. If this is the case, the good doctor is creating millions of people in a new reality just so a small number can be blown up on a train and millions can be maimed or killed in Chicago when the dirty bomb explodes. This act of creation and death is justified because it’s expedient to save our people. It would be less immoral if the alternate realities already exist. Now all we’re doing is exploiting what’s inevitable for them, so that we can avoid the same fate.

No matter how it works, in each of the eight minute insertions, Colter Stevens learns about the people in his section of the train. He does this by being prepared to beat them up and, if necessary, shoot to kill. We’re not supposed to care because the people we see only have eight minutes to live. What happens to them is irrelevant in the larger scale of things. In the midst of his investigating, Colter Stevens finds himself attracted to Christina Warren, played by Michelle Monaghan. He decides he should try to save her. This is interesting because, should he succeed, one person surviving the train explosion will produce a major divergence of the realities. That need not concern our timeline, of course. It just means there will never be any chance of going there again as this person now interacts with thousands of people during her lifetime, thereby moving that reality ever further away from ours.

With Colter Stevens dying every eight minutes, he develops psychological problems. Encouraging him to keep going is the pivotal Colleen Goodwin played with quite remarkable sensitivity by Vera Farmiga. Without someone strong in this role, the film would collapse. She’s pitch perfect throughout and gives the film unexpected weight.

This is the stand-out science fiction film so far this year. Jake Gyllenhaal strives valiantly in a slightly thankless role while everyone else, led by Vera Farmiga, rallies round and produces an excellent ensemble piece. It’s a clever script by Ben Ripley allowing the scenario on the train to continuously evolve and expand. For once, Ripley has produced something better than films about sex-crazed aliens, with the whole thing beautifully directed by Duncan Jones, who seems to be making a name for himself rather fast. All in all, Source Code is excellent viewing for anyone who likes science fiction which follows through to the implications of our actions no matter how immoral.

Stop reading here if you don’t want a discussion of what actually happens.

We get this far by suspending disbelief and accept the arrest of the bomber in our timeline. Not being sure how the machine works, we may have to thank Dr Rutledge for destroying Chicago in perhaps more than one hundred other realities depending on how many times Colter Stevens iterates through his eight minute loops. But we are safe. Our Earth’s authorities are delighted with the outcome and can’t wait to use the machine again. Before they embark on new threats, I sincerely hope the Government intends to use the machine to save as many alternate versions of Chicago as possible. This would be the moral step, maximising the benefit of this invention for all realities. We would want other realities to save us if they could, so every Dr Rutledge should be arguing for his Colter Stevens to help others before he helps himself. Sadly, we see Dr Rutledge rubbing his hands and only speculating on what his next triumph will be, confirming the general lack of morality in this project. This is selfishness personified, a sauve qui peut approach to life.

Perhaps anticipating how he will be used and taking everything he has learned about the train, Colter Stevens now knows enough to prevent the train from blowing up. He therefore persuades Colleen Goodwin to send him in one last time to save at least one Chicago. At the end of this eight minutes insertion, she’s to turn off his life support and let him die. This she does. The result is presumably an arrest with her sent off to die in the Marine Corps Brig in Quantico.

After the freeze frame, we are in the alternate reality where Colter Stevens saves Chicago, gets the girl, and sets off for a new life with her. What makes the ending initially appear so pleasing is the text message he sends to Colleen Goodwin in this new reality. For, yes, there’s an identical project in this reality with a version of himself waiting to be deployed to solve a major crime and avert catastrophe. This message primes Colleen Goodwin to encourage Colter Stevens. Not only can he “save the day” no matter where he’s sent, but he can also escape and find a new life for himself in an alternate reality. So each reality may be said to offer Colter Stevens hope, no matter how desperate things may seem. No-one can ask for more than that in any reality. Let’s not go into whether our hero could sustain a convincing impersonation of a man in that reality, once it’s confirmed he can stay with the new identity. There’s also an unresolved paradox because, if Dr Rutledge’s technology depends on the target man dying, he no longer dies, i.e. the transfer should not work.

Now let’s come to the really big question. Colter Stevens knows he displaces the mind of the man in the target body. Let’s say he believes the mind of the teacher is transferred into his body. When he persuades Colleen Goodwin to switch off the life support, he intends Goodwin to kill the teacher so that the replacement is permanent. In my book, that makes Colter Stevens and Colleen Goodwin murderers. However, no matter what he believes about where the mind of the teacher goes, the clear intention is to kill that mind so that our “hero” can have a happy ending. There used to be a morality code in Hollywood. It was known as the Hays Code. Although this was predominantly concerned with sexual and, to some extent, political content, there was a general view that motion pictures should not show criminals benefitting from their crimes. Under the Code, this ending could not have been added after the freeze frame. The rule used to be that criminals should be punished. While this is, no doubt, unacceptably black and white for our relativist age, I’m surprised a stone-cold killer should be shown enjoying his stolen life in the final frames. I’m not sure what message this is sending to our impressionable young.

Source Code (2011) has been shortlisted for the Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation 2011 and for the 2012 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation — Long.