Archive

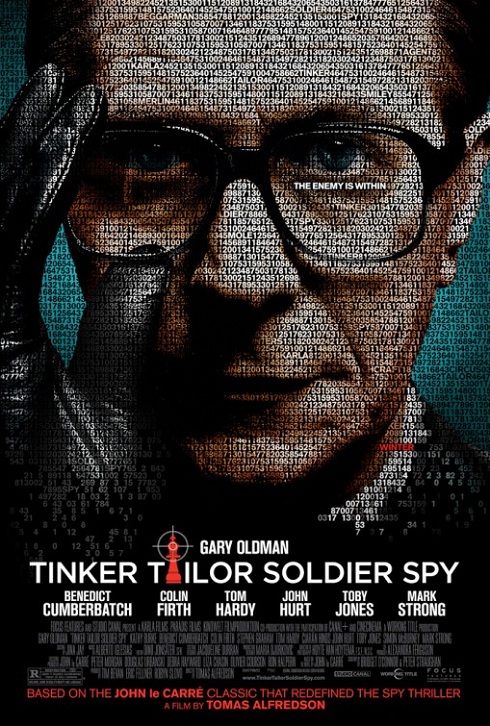

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy sees Oscar nominations for Gary Oldman as George Smiley, for Peter Straughan and Bridget O’Connor (now sadly dead) as the scriptwriters tasked with adapting the novel by John Le Carré, and Alberto Iglesias for the music. It’s been variously nominated for awards by BAFTA, BIFA and others in foreign parts. To that extent, critics and those who vote for awards seem convinced this is a film of great merit. This is not necessarily reflected in its box office performance where it has taken only about $65 million around the world. Such relatively poor performance might indicate the potential audience views it as an art house film and of limited interest. The higher rating, undeserved in my view, may also be a deterrent.

Naturally I watched the BBC serialisation back in 1979. Checking back, it was in seven parts although, apparently a slightly shorter six-part version has been produced for distribution by DVDs. This means a sizeable percentage of the audience will have seen Alec Guinness play George Smiley. Not having read the book, I remember how I worked out who the mole must be long before he was unmasked. It was the best actor not to have been given major screen time. Naturally, Alec Guinness and the actor involved had a long conversation at the end. So, since all the awards have focused on the Oldman performance, I suppose that’s the best place to start. As a character, Smiley is supposed to be quiet if not taciturn. This always represents something of a challenge to actors who prefer to be seen doing things, even if only speaking. The solution comes from the director Tomas Alfredson and the scriptwriters who have included extended flashbacks to a party held at the Circus, particularly showing where Smiley becomes aware of his wife’s infidelity with another of the spies, getting him drunk to tell the story of his meeting with Karla (the lighting is particularly effective in cloaking half his face in shadow), and allowing him to seem more of an action figure when threatening to send Toby Esterhase (David Dencik) out of the country. The significant editing down of the plot also means there are fewer pauses between the odd questions he asks and the instructions he issues. For all this, the performance is slightly monotonous. When you might expect him to unwind a little, as with Connie Sachs (Kathy Burke), there’s very little animation. Although the performance fits the character and is nicely nuanced with very small movements to indicate an internal life, I prefer Alec Guinness.

Now as to the cinematography from Hoyte Van Hoytema, this is beautifully shot with muted tones as clouds of smoke drift across rooms holding anxious men. By using rather flat lighting, it creates a sense of the paranoia that was pervasive at the time. Unfortunately, all the really good news stops there. The major problem comes with the constraint of time in the cinema. Although I have not read the book, it’s obvious from the television adaptation that it’s a subtle work, packed with detail on the spycraft, considering the art of being a spy at a difficult political time, while pursuing a challenging investigation. You cannot take something so multilayered and condense it down to two hours without sacrificing a lot.

In this case, the process of editing has produced a focus on the investigation from Smiley’s perspective with very little time given to establish the characters of the suspects. Ironically, you get to see more of foot-soldier Peter Guillam (Benedict Cumberbatch) and Control (John Hurt) after he dies, than you do of Percy Alleline (Toby Jones), Roy Bland (Ciaran Hinds) or Bill Haydon (Colin Firth). This makes the plot more difficult to follow. I don’t mind a more impressionistic approach to adaptations when the subject matter is more suitable. But the investigation to identify a possible spy is not something you can gloss. It depends on details. When those details are missing, even the most dedicated viewer will struggle unless he or she has read the book or seen the longer BBC adaptation. Frankly, I would have ditched the party sequences to allow more time to establish a clearer context for the investigation and a better view of the suspects.

This is not to deny this is a very good film, but it does explain why it has not been shortlisted for best film in most of the awards. Even in the BAFTAs where you might have expected the maximum support, it failed to win “best”. Overall, it’s most successful when all it’s trying to do is create a mood of the times. There’s a moment of sadness marking the passing of an era and signalling a possible need to bring in a new generation when Kathy Burke as Connie Sachs says of WWII, “At least that was a real war. English men could be proud then.” So go and see Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy if you know and like the story, or if you’re prepared to invest considerable effort in following the backstory as it emerges through the flashbacks. As cinema adaptations go, it’s very good. If the production team had had more time to play with, it could have been better. There is a slight element of tragedy here. The producers assembled a high class cast and then did not give them enough to do.

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Murder on the Orient Express (2010)

Murder on the Orient Express (2010) is a joint production of ITV Studios and WGBH Boston staring David Suchet as Hercule Poirot. As an adaptation of the original novel by Agatha Christie, this is an interesting attempt to reframe the story as a moral dilemma. It begins with Poirot conducting an investigation in Palestine which is abruptly concluded by the suicide of a man whom he was accusing of involvement in a murder. Regardless whether he was correct in his accusation, the immediacy of the man’s response to snatch up a gun, his blood splattering over Poirot, left Poirot with the sense he did not handle the entire affair well. When we get to Istanbul, a further street scene is added to the plot as he watches an angry crowd stone an adulteress. As viewers, we’re supposed to make a judgement about the act of retribution on behalf of the wronged husband. In this Turkish culture, stoning is the accepted form of punishment but we’re expected to condemn it as barbaric. We’re supposed to be predisposed to condemn vigilanteism by a crowd regardless of the perceived provocation.

There’s quite a heavy religious element running through this adaptation with Poirot shown praying and saying the rosary as a good Catholic should, except. . . Although Poirot almost certainly was a Catholic — most Belgians of that time would have been — there’s no real sign of religiosity in the particular book or, more generally, in the series as written by Agatha Christie. This is one episode of a long-running series of television adaptations and, although it’s an effective element in this one episode, it does rather skew the normal characterisation of the man. In the book, Poirot is a man of compassion who, while he does not approve the murder, agrees to allow the murderer(s) to go free. This version does not feel quite right.

If Poirot is inflexibly moralistic and we apply the tenets of the religion at that time, why should he decide to look the other way? The murderer(s) have paid their victim the compliment of imitation. Indeed, their premeditation probably makes them even less sympathetic than their victim unless we’re to assume the kidnapper always intended to kill the girl he abducted. A Catholic of that period would have been self-righteous and lack the will to lie to the police. The idea Poirot would cover up the crime and then walk away praying the rosary in the hope it would somehow wash away his sin is somewhat extraordinary. If the adaptation does offer a reason for this decision, we should consider Poirot’s refusal to act as the man’s bodyguard. He has seen the man in the hotel and observed him on the train. Regardless whether he recognises him as Cassetti, Poirot turns down the offer of a large sum to protect him. So, by omission, Poirot has some responsibility for the man’s death. He could have saved him but, as in the parable of the Good Samaritan, chose to walk on the other side. Looking at the adaptations still to come to the small screen, this characterisation of Poirot could foreshadow Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case. This more intense Catholicism and sense of guilt would fit more comfortably into the final mystery where much of the man’s narcissistic pride has evaporated and the little grey cells have lost some of their certainty.

In this respect, it’s interesting to compare Poirot with Jacques Futrelle’s creation Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen. As a detective, this man aspires to being a “calculating machine”. There’s no light or dark in his scientific approach to solving problems. He enjoys the challenge and leaves it to the world to deal with the morally grey areas in ascribing degrees of blameworthiness to the criminals. In most of his cases, Poirot is similarly free of moral doubts. He hands his solutions over to the police and courts, and rarely seems troubled by the human consequences of his work. This makes this adaptation somewhat heavy-handed. For example, at least one of the murders asserts the Lord was on her side. If this was believed real, the detective must step aside to allow divine retribution to prevail. In this battle between scientific methods of detection and religion, Sherlock Holmes is more clearly willing to work outside the law and exercise a personal judgement for mercy. Only once, in “Speckled Band”, does he flirt with the idea of taking the law into his own hands and dispatching the criminal. For all his trappings of science, Holmes remains a man rooted in the culture of his time. He’s more inclined to see the potential for destructiveness if pure science prevails over morality. It requires immense arrogance on the part of scientists or detectives using scientific methods, to assert only they can lead humanity to a new life of happiness.

Returning to this television adaptation and looking past the attempt to convert a murder mystery into a modern morality tale, we do find a nicely claustrophobic production. There’s been a very real attempt to put the characters on top of each other in the different compartments with little room to swing a small proverbial cat. Even the dining car feels narrow and cramped with everyone huddling together. This is reinforced by limited lighting with shadows cast into the hollows of eyes and sunken cheeks as sleep comes hard and the cold creeps in from the snow drifts outside. Curiously, the cast is not asked to do much. They are shuffled around and, when asked, offer the usual evasions. I suppose the point is to leave them as faceless as the crowd who stoned the adulteress. Only Toby Jones as Cassetti is allowed enough time to establish himself as thoroughly unlikeable.

So, overall, Murder on the Orient Express is an interesting effort. It seems to have offended the Christie purists but there’s nothing inherently wrong with an adaptation that challenges conventional wisdom. For me, it’s a moderately successful version of a classic detective story.

For reviews of other Agatha Christie stories and novels, see:

Agatha Christie’s Marple (2004) — the first three episodes

Agatha Christie’s Marple (2005) — the second set of three episodes

Agatha Christie’s Marple (2006) — the third set of three episodes

Agatha Christie’s Marple (2007) — the final set of three episodes

Agatha Christie’s Marple: The Blue Geranium (2010)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: A Caribbean Mystery (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: Endless Night (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: Greenshaw’s Folly (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side (2010)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: Murder is Easy (2009)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: The Pale Horse (2010)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: A Pocket Full of Rye (2008)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: The Secret of Chimneys (2010)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: They Do It with Mirrors (2009)

Agatha Christie’s Marple: Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? (2009)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb (1993)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman (1993)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Big Four (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Case of the Missing Will (1993)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Chocolate Box (1993)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Clocks (2009)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Curtain. Poirot’s Last Case (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Dead Man’s Folly (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Dead Man’s Mirror (1993)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Elephants Can Remember (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Hallowe’en Party (2010)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan (1993)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Labours of Hercules (2013)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Three Act Tragedy (2011)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Underdog (1993)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Yellow Iris (1993)