Archive

The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

I need to start with a short explanation of why I’m not going to comment directly on the Colorado massacre. This is a review blog and not concerned with real-world tragedy or the politics of gun control. The only relevant issue is briefly to consider whether writers and those who make films or television programs should be held accountable if people act out what they have read or seen. I’ve long been sceptical of any link between a person reading about specific behaviour or viewing that behaviour on a screen, and the decision to act it out. Since the introduction of the printing press, there have been millions of books from cultures all around the world in which people have been described engaging in a wide range of activities. When we add in films and television programs, and widen the boundaries of taste, we can observe an extraordinary diversity of human behaviour. At moments like this, we’re prompted to ask whether people exposed to depictions of violence become violent but that rather ignores the more general question of cause and effect.

Abuse or aggression in the home is said to shape a child’s upbringing and make him or her more likely to be aggressive in the future. Naturally not all victimised or abused children become aggressive or abusive when they grow up. But some do. During their subsequent trials, the tendency to abuse others is said to be behaviour learned by experiencing how authority figures act. In other words, the socialisation process involves effects from the relationships within the family and the home environment, the interaction with authority figures, the pressures from peers, and a host of other factors. No-one would pull out a single episode in a television series such as Criminal Minds and blame it. Indeed, the problem in designing scientific research into whether there’s any link between violence observed and violence in action, is that showing people stimulus material and trying to measure their reaction takes the stimulus material out of context. Books, films and television do not exist in a social vacuum. Is it to be suggested we should not see news of the shooting in Aurora because this may incite copycat shootings? Every day, the news and comment media carry supposedly factual reports of criminal activity and other acts of social deviancy. There are tens of thousands of books which contain fictionalised versions of what we can imagine protagonists and antagonists doing to themselves or others. We should not censor the information that flows through our culture, nor seek to blame those who originate any individual item in the discourse as a whole. Indeed, news from Aurora would be a positive force for good if everyone focused on condemning the violence and discussing how public policy can be changed to reduce the chances of it happening again. The less violence is glorified and the more the peer group disapproves its use, the less the use of violence is seen as justified. If there are no rewards for the use of violence, there are fewer incentives for people to be violent.

At this point I need to start talking about The Dark Knight Rises (2012) whose contribution to this debate is equivocal. Making a vigilante into a hero plays a dangerous social game. In some senses, it’s showing society taking a positive benefit from the activities of a man who never feels constrained by the usual social conventions. For more than one-thousand years, laws have tried to steer people away from individual action, outlawing blood feuds and criminalising revenge. We have been persuaded the peace and order in society is the greater good and surrendered our individual rights to the law enforcement agencies and the courts. In the film, the Dent Act has been used to deprive alleged criminals of due process. They have been locked away without a right to a fair trial on the facts, and without a proper process for sentencing. In terms of civil liberties, the cure has been worse than the disease. More importantly, the policy is based on the lie that Batman wrongly killed Harvey Dent and so represents the worst political expediency in action. Ironically this gives Bane some moral justification for leading a revolution and storming the local equivalent of the Bastille to release the prisoners. It’s just unfortunate that many of those released are dangerous and probably deserved to be locked up indefinitely. The later scenes showing the revolutionary courts in action mimic those set up by the Committee of Public Safety in France during the Reign of Terror and set up the power of the quote from A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens at the end. It pays the framers of the Dent Act the complement of imitation. Both sides are completely arbitrary in their oppression of those they dislike.

Against this background, we need to understand the roles people play. Daggert (Ben Mendelsohn) is the ultimately corrupt politician who uses his position to advance his own fortune. Commissioner Gordon (Gary Oldman) is the honest cop who feels guilt that he allowed the agenda to get out of his control. He knows the means do not justify the ends. Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway) has opted for crime as the means to achieve her ends, but is wise enough to understand there have to be limits and ways to find redemption. She makes a pleasing counterpoint to the self-absorbed Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) who can’t ride down the street on his new bike without breaking half-a-dozen traffic laws every block. Miranda Tate (Marion Cotillard) represents a single-minded focus on the belief that humanity must somehow rid itself of corruption whether through projects to deliver low-cost energy to Gotham City or other ways. Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is the voice of the young generation. Tired of being marginalised and victimised by older placeholders who have no accountability when things go wrong, he wants to get things done even if he ends up killing a few people on the way. But the most interesting figure is Alfred (Michael Caine) who gives a performance of great power as a paternal Everyman. He wants the best for young Master Bruce but not at the expense of Gotham City. When Batman distracts the police from chasing Bane and inspires mayhem, he shakes his head at the price society must pay for indisciplined interference. Would it not be better for Bruce Wayne to be actively involved in using his vast financial resources to help Gotham City out of the mess? Indeed, in Batman Begins (2005) the terrorist organisation called League of Shadows executed Bruce Wayne’s father because his philanthropy was so effective in stabilising the community. Alfred becomes disillusioned and leaves Bruce Wayne, the man he has loved as his own son. We are encouraged to see Bruce Wayne as losing his moral compass. He wallows in the arrogant delusion he can solve all his own problems (and those of Gotham City) by putting the suit back on.

Bane (Tom Hardy) is all business. He’s not showy or extravagant. His initial entry into the city is as a fixer for Daggert but, of course, he’s not a mere criminal. Nor, indeed, is he a true revolutionary. He’s a nicely complicated man who finds himself driven to destroy Gotham City. This understated performance makes a nice counterpoint to Batman’s more extravagant and flamboyant style. Whereas Bane lumbers around looking as if he’s just spent the night sleeping in his sheepskin jacket, Batman has to turn up on novel motorbikes or in futuristic flying machines looking dapper in his body armour. Bane is brutal and effective. With no knee or elbow joint in full working order, and with eight years of inactivity behind him, Bruce Wayne punches with the authority of a schoolgirl. Bruce Wayne overreaches because he believes in the myth of his own invincibility. He therefore has to learn what’s most important to him as his life lies in ruins. That the ending shows nobility of spirit is confirmation that he was, at heart, a good man. Alfred is justly proud of him.

However, I fear the film itself is not a complete success. As a piece of narrative fitting into the format of a trilogy, it’s a masterpiece. I see Christopher Nolan and his bother Jonathan Nolan who jointly wrote the screenplay, allowed a full novelisation by Greg Cox. I suspect it all works rather better on paper. The key difficulty is the need for the action to reflect the passage of at least five months. If a filmmaker is relying on the tired old device of the bomb counting down from 10, we only have a few seconds to watch the hero decide to cut the blue wire. This used to be exciting. But when the countdown is measured in months, it loses its dynamic force. As we watch Bruce Wayne rebuild his body, everything connected with Gotham City is fudged. How do all these policemen survive underground? Where does all the food come from to keep the population alive? How are water and power supplies maintained during the winter? And so on? Although the CGI of the flying bat is quite impressive in the final sequences, it was something I admired at a technical level more than found exciting. Oh dear, I was saying to myself, Gordon’s got himself into another of these silly script situations where he drops the gizmo and gets thrown around the inside of a truck like an action man toy. It’s all been seen before. Yes, it’s put together with all the skill we would expect of Nolan but. . .

Make no mistake, The Dark Knight Rises is a very impressive film and because it thoughtfully addresses some very interesting ideas of contemporary importance about our reaction to criminal behaviour in general and terrorism in particular, it deserves to reach the widest possible audience, i.e. it’s not just a fanboy comic book film. But you shouldn’t go expecting it to be non-stop entertainment in the wham/bam style of blockbuster cinema. It take its time and, in the end, this gives the film more emotional depth.

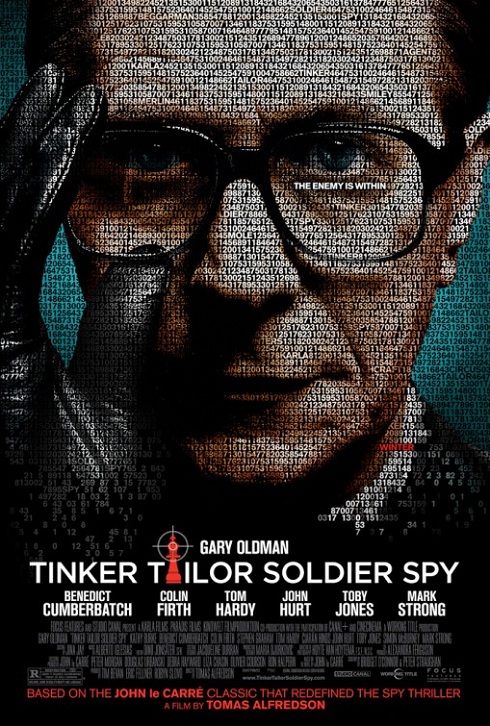

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy sees Oscar nominations for Gary Oldman as George Smiley, for Peter Straughan and Bridget O’Connor (now sadly dead) as the scriptwriters tasked with adapting the novel by John Le Carré, and Alberto Iglesias for the music. It’s been variously nominated for awards by BAFTA, BIFA and others in foreign parts. To that extent, critics and those who vote for awards seem convinced this is a film of great merit. This is not necessarily reflected in its box office performance where it has taken only about $65 million around the world. Such relatively poor performance might indicate the potential audience views it as an art house film and of limited interest. The higher rating, undeserved in my view, may also be a deterrent.

Naturally I watched the BBC serialisation back in 1979. Checking back, it was in seven parts although, apparently a slightly shorter six-part version has been produced for distribution by DVDs. This means a sizeable percentage of the audience will have seen Alec Guinness play George Smiley. Not having read the book, I remember how I worked out who the mole must be long before he was unmasked. It was the best actor not to have been given major screen time. Naturally, Alec Guinness and the actor involved had a long conversation at the end. So, since all the awards have focused on the Oldman performance, I suppose that’s the best place to start. As a character, Smiley is supposed to be quiet if not taciturn. This always represents something of a challenge to actors who prefer to be seen doing things, even if only speaking. The solution comes from the director Tomas Alfredson and the scriptwriters who have included extended flashbacks to a party held at the Circus, particularly showing where Smiley becomes aware of his wife’s infidelity with another of the spies, getting him drunk to tell the story of his meeting with Karla (the lighting is particularly effective in cloaking half his face in shadow), and allowing him to seem more of an action figure when threatening to send Toby Esterhase (David Dencik) out of the country. The significant editing down of the plot also means there are fewer pauses between the odd questions he asks and the instructions he issues. For all this, the performance is slightly monotonous. When you might expect him to unwind a little, as with Connie Sachs (Kathy Burke), there’s very little animation. Although the performance fits the character and is nicely nuanced with very small movements to indicate an internal life, I prefer Alec Guinness.

Now as to the cinematography from Hoyte Van Hoytema, this is beautifully shot with muted tones as clouds of smoke drift across rooms holding anxious men. By using rather flat lighting, it creates a sense of the paranoia that was pervasive at the time. Unfortunately, all the really good news stops there. The major problem comes with the constraint of time in the cinema. Although I have not read the book, it’s obvious from the television adaptation that it’s a subtle work, packed with detail on the spycraft, considering the art of being a spy at a difficult political time, while pursuing a challenging investigation. You cannot take something so multilayered and condense it down to two hours without sacrificing a lot.

In this case, the process of editing has produced a focus on the investigation from Smiley’s perspective with very little time given to establish the characters of the suspects. Ironically, you get to see more of foot-soldier Peter Guillam (Benedict Cumberbatch) and Control (John Hurt) after he dies, than you do of Percy Alleline (Toby Jones), Roy Bland (Ciaran Hinds) or Bill Haydon (Colin Firth). This makes the plot more difficult to follow. I don’t mind a more impressionistic approach to adaptations when the subject matter is more suitable. But the investigation to identify a possible spy is not something you can gloss. It depends on details. When those details are missing, even the most dedicated viewer will struggle unless he or she has read the book or seen the longer BBC adaptation. Frankly, I would have ditched the party sequences to allow more time to establish a clearer context for the investigation and a better view of the suspects.

This is not to deny this is a very good film, but it does explain why it has not been shortlisted for best film in most of the awards. Even in the BAFTAs where you might have expected the maximum support, it failed to win “best”. Overall, it’s most successful when all it’s trying to do is create a mood of the times. There’s a moment of sadness marking the passing of an era and signalling a possible need to bring in a new generation when Kathy Burke as Connie Sachs says of WWII, “At least that was a real war. English men could be proud then.” So go and see Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy if you know and like the story, or if you’re prepared to invest considerable effort in following the backstory as it emerges through the flashbacks. As cinema adaptations go, it’s very good. If the production team had had more time to play with, it could have been better. There is a slight element of tragedy here. The producers assembled a high class cast and then did not give them enough to do.